The Bluestockings: Chapter Four

"...sometimes even the best people, the ones who seem to set the standard for goodness and truth, can turn out to be more flawed than anyone thought possible."

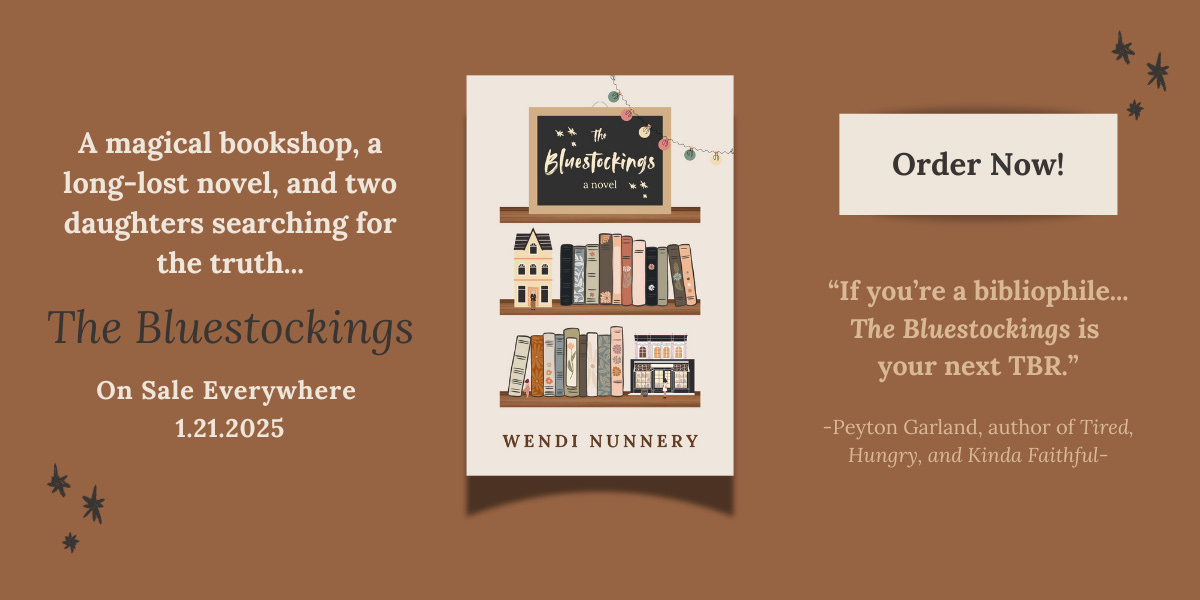

Welcome to The Nook! The Bluestockings is my latest novel, which I’m releasing in serial form one chapter at a time. These posts are free for you to read, but they were not free for me to produce. If you’d like to support my work, please consider becoming a paid subscriber or purchasing your own paperback/Kindle copy of The Bluestockings. Thanks for being here!

Ruby

The first week of Maggie’s visit was a turbulent one.

Ruby was so used to the perpetual quiet of her home that the increased volume caused by Maggie’s lead feet on the floor above her, her enthusiastic chewing at the table, or the constant buzzing of her cell phone grated on Ruby’s last nerves. The girl had no manners at all, and Ruby was not shy about sharing her opinions on the matter.

“You might want to ease up on her a bit, dear, if you plan on getting through her visit in one piece,” Marianne said, her voice gentle but firm.

Ruby sighed as she shuffled to her father’s old desk in the library. It helped her to feel more in control when she sat in his old leather chair, soft as butter from decades of use and as strong as he had once been.

“I’m not the one you need to worry about, Marianne,” Ruby stated. “Margaret is thirteen, not three. If she cannot respect the basic rules of consideration for others in my house, then there will be consequences.”

Marianne cocked her head to the side and pierced Ruby with a sharp look. Ruby began to squirm under the intensity of her glare. “Ruby Hurst. I know we’ve never considered ourselves to be friends, exactly, but in all my years of working for you, I’ve never known you to be unkind. Stern, yes. Particular? Absolutely. But mean for the sake of meanness? Never.”

“Until now,” Ruby finished for her.

Her housekeeper shrugged and continued dusting the bookshelves.

“Go on,” Ruby insisted. “You can say it.” Marianne refused to reply, but Ruby got the message clear enough.

She sat back in her father’s chair and ran her fingers over the lines etched onto its surface. She could picture him there, hard at work, while she pestered him with questions about the books on the shelf. She had been forever curious about the stories they contained. At eight years old, he finally let Ruby have free rein of the library, and she had devoured the books, one after the other. For years, her favorite had been Flower Children: The Little Cousins of the Field and Garden, a small, charming book that contained illustrations of children dressed as flowers, each accompanied by a clever verse. They were easy to memorize. In the spring and summer, Ruby would take Flower Children outside and roam the estate in search of blooms she could identify by verse. She could spot the difference between pansies and peonies, sweet alyssum and apple blossom, and knew which flowers were toxic or safe to pluck from their stems.

If she closed her eyes and concentrated hard, the image of Ruby’s mother seated on a blanket beneath the oak trees, her face lifted to the sun, could be conjured. It was hazy now, like looking through a foggy window, but the feeling of warmth and safety that had flowed through Ruby’s tiny body on that day remained as fresh now as it was seventy- five years ago. The flower book had been a gift from her mother, and some joys just could not be forgotten. No matter how many years had passed.

The same was true of sorrows.

Marianne completed her tasks in the library and left Ruby seated like a scolded child in her father’s chair. She found it hard to argue with her housekeeper’s logic, and yet she returned to her time-worn reasons for strict boundaries like one would return to a familiar coat in the winter. They kept her safe from the icy bite of death. With them, she was safe to enjoy the world around her without suffering the inevitable despair that followed closeness with other people. She’d had quite enough of that in her life.

Ruby would continue with her limited time on earth the way she had since her father had died and left her with his money and secrets. It was too late now for her to be exhilarated by life anyhow. Those days had gone the way of her mother, her father, her sister, and her brother. And they would never return.

The front door slammed, and Ruby started at the sound. Maggie was back from walking Marianne’s dog, Danger. He was a Dachshund puppy, no bigger than Ruby’s foot.

“Marianne!” Ruby called out as she slipped off her sneakers, leash in hand. Danger pulled towards the library, but Maggie scooped him up before Ruby could protest.

Marianne poked her head out from the parlor. “I’m here,” she said.

“He pooped once and peed twice,” Maggie squealed with the same enthusiasm one would expect from a lottery win. “You’re such a good boy, aren’t you, Danger?” She pressed her face up close to the dog’s, and he licked her nose. Ruby looked heavenward.

“Lord, help me,” she sighed. “Margaret, please take that dog back to Marianne’s cottage. I don’t want it doing either of those things on my rugs.”

“‘It’ is a ‘he,’” said Maggie with another coo at the puppy. “And I am a Maggie, not a Margaret.”

“Regardless,” Ruby continued. “Do as I say.”

Maggie gave a dramatic sigh and put Danger down. “Let’s go, buddy. I’ll come visit you later and bring treats.”

“You’re a doll,” Marianne said to the girl as she led Danger out the front door again. “He’s going to want to come home with you in January if you keep this up.”

“Fine by me!” Maggie replied.

“Fine by me, too,” Ruby grumbled. Maggie laughed—a bright, open sound that touched a tender spot in Ruby’s chest—and closed the door. Ruby rubbed her breastbone as though in pain. Maggie’s laugh conjured memories of Ruby’s father and his big, lovely guffaw.

Another lifetime.

Her father, William, had lavished Ruby with affection. He called her his Daffodil after Ruby had declared it her favorite flower and picked every single one within a three-acre radius of the house. It was a nickname that continued until the day he died. Ruby had grown up under the bright spotlight of his adoration. He often reminded her that it was his duty to love her twice as much since he had to show her the love of two parents. It seemed a simple goal for a man with such a gregarious personality and large family inheritance, even if Ruby—in her confusion and grief—hadn’t made it easy for him.

She hadn’t made it easy for her stepmother or younger siblings, either. When William married Jeanice Russell, twelve years his junior, in 1952, she had been eager to start a family with him. A new family.

Jeanice—or Jean as Ruby had called her—had never known what to make of Ruby. She was eight years old when William married Jean, and by then Ruby was well set in her quiet bitterness. Though Ruby had desperately longed for a mother, she only longed for her own. Jean had fallen short of that expectation despite her attempts to carve out a space in Ruby’s heart. It wasn’t long before Jean gave William two more children to dote on— Ruby’s younger sister, Caroline, and younger brother, Edward. Before they were out of elementary school, Ruby was well on her way to college.

On her visits home from Georgia Teachers College, she’d sit at the dining table and watch her family tease one another and share stories that Ruby knew little about. It seemed to her that they made a complete set, the four of them, just as they were. She loved them all with a fierceness, and yet she was not one of them. Not in the way her father had hoped, nor in the way she could see Caroline and Edward were.

Oh, but Ruby had been beautiful. When most girls were just on the cusp of breasts and hips, Ruby already had a full set of both. Her long, full locks were once the color of a setting sunset just before it disappeared over the horizon. She’d been the envy of all her peers. Her good looks made her an obvious focal point everywhere Ruby went. She became quite well known in and around Hawthorn for the bevy of pageant titles she won during her years of competition. People were eager to forget their opinions of her history once they set their sights on her beauty. Crowns and sashes and prize money became the easy boost to her confidence that Ruby could not seem to find within her family, no matter how much her father praised her or how her siblings admired her. Ruby was an outsider with a whole separate identity that didn’t include them. The memory of her mother and the hole within Ruby’s heart simply could not be forgotten.

She had gotten close to forgetting once. So very close. Then that hope had slipped away, too, and Ruby had given up on hope altogether.

Marianne returned to the library and knocked on the door frame. “Ruby, you got a minute?”

Pulled out of her reverie, Ruby shook off the memories and clasped her hands together on the desk. “Unfortunately, I have more minutes than I would like.”

Her housekeeper huffed. “Having a pity party today, are we?” she asked, a note of humor in her charming accent.

“Not pity. Just facts,” Ruby replied. “What do you need?”

Marianne brightened. “I introduced Maggie to Eleanor Black yesterday. They hit it off, and Maggie invited Eleanor to come over tonight. I’ve already spoken with Eleanor’s dad about it, and he didn’t mind. I think he wants Eleanor to get out of the bookstore more often and make some friends. Lord knows Maggie needs someone her age around.”

Ruby hadn’t moved a single eyelash while Marianne spoke. “And you want to know what I think?”

“I know you don’t like strangers, but it seems like a good idea if you want to keep Maggie occupied and out of trouble while she’s here. She can’t just sit on her phone all day.”

It did seem like a good idea, except for the fact that one pubescent child in the house was already one too many. Two was just asking for it.

“I wish you would have spoken with me first, Marianne,” Ruby said, pinching the bridge of her nose. “It seems the decision has already been made.”

Marianne had the good sense to look sheepish. “I knew you would say no,” she admitted.

Ruby scoffed. “Better to ask for forgiveness than ask for permission, then, am I correct?”

“I have too much to do around here, Ruby,” Marianne countered. She put her hands on her hips and glared at her employer. “I can’t babysit Maggie, much as I like having her around, and you certainly aren’t going to do it. She needs a friend. I know it’s been a long time since you were thirteen, but try and remember for her sake. Maggie’s been dropped here on her Christmas break while her mum moves out of the only home she’s ever known and divorces her father. Think of how she must feel right now.”

To tell the truth, Ruby hadn’t much considered how Maggie might be feeling. She tried not to think of her at all.

Her shoulders slumped as she realized Marianne was right. How inconvenient it was to have such a compassionate housekeeper. “Fine, fine,” she finally said, biting off each word. “Just...do whatever needs to be done so they don’t get in my way.”

Marianne smirked and shook her head. “Ruby Hurst, you are one of a kind.”

Don’t I know it, Ruby thought to herself as Marianne headed back to the parlor.

Her whole life had been one big sideshow. Ruby had made peace with people’s whispers and stares as a child. Her mother’s mysterious death had only added to the intrigue, but as she grew older and the town’s expectations of what a beautiful, rich woman should do with her life failed to come to fruition, their opinion of Ruby Hurst had soured. As the years passed, Ruby hid herself away, and the people who might have once called her friend were now sleeping in their graves. She’d become an old crone with better style, a Miss Havisham in a lonely mansion, and she no longer gave anyone reasons to stare at her because she stayed as far away from her hometown as she could. Whatever Ruby needed, Marianne or Ben had always brought to her.

Ruby pulled herself up from her father’s desk and ran her wrinkled hand across the wood. Too much sadness lived in her heart for Ruby to care much what people thought of her or to try and restore what had been lost. She shuffled over to the stairs and looked up, suddenly exhausted. With great effort, she pulled herself up them one by one, the weight of her memories an anvil on her thin, narrow shoulders. Then she padded down the hall to her bedroom, taking a seat in the large bay window across from her bed.

Fresh anger at everyone, from her mother and father to Maggie and even Eleanor Black, lit a fire in her gut. She stoked it with her self-pity and uncharitable thoughts as she glared out at the quiet world around her childhood home. The live oak trees looked sad to her now; their branches hung low as though they, too, were tired of holding up the weight of all the Hurst family troubles. All of Ruby’s troubles.

Had any of it been worth what her father had given? What she had given?

Ruby squeezed her eyes shut and waited for the prickling in her nose to stop. She would not cry.

Even after twenty-five years, she missed her father. She longed to hear the velvet bass of his voice, his affectionate teasing. Despite her anger at all the unanswered questions he’d left behind for Ruby to solve alone, she would never regret that he had belonged to her.

Outside, holiday lights Benjamin had strung around the intricate porch railings conjured thoughts of Ruby’s last Christmas with William. Caroline had died some years before, and Edward had spent the holiday at home in Virginia, so Ruby and her father were there to celebrate together. Ruby worked all day on a delicious Christmas feast. The kitchen was a mess of flour, vegetable ends, and dirty mixing bowls, but she managed to create a more-than-palatable roast turkey. She paired it with homemade dressing and gravy, squash casserole, and pumpkin pie from Jean’s old recipe book that was still stowed away in the cupboard.

William was even older than Ruby was now. A decade-old prostate cancer diagnosis, which had lain dormant, had chosen that year to finally flourish and spread to the rest of his brawny, graceful body. It was the anniversary of Ruby’s mother’s death, a day that never failed to haunt them both. Over dinner, they had spoken of Alice in quiet reverence, alone together in their too-brief memories of her. They spoke of so many things that night. It was in that conversation William had given Ruby his estate, in word before it was made official in deed.

Then, he confessed to a secret that changed everything.

Strangely enough, the worst part about William’s confession wasn’t even the truth. No, the worst part was the transformation that occurred in Ruby’s soul the moment she heard his words. It was the realization that sometimes even the best people, the ones who seem to set the standard for goodness and truth, can turn out to be more flawed than anyone thought possible.

William died two short weeks later. Ruby walked around in a daze then, shell-shocked over both the loss of her father and the conversations she had still hoped to have with him. The funeral a few days after was practically a spectator sport. The entire town of Hawthorn was in attendance, alongside many of Savannah’s elite who wanted to see and be seen alongside someone from the infamous Hurst family. Even a dead or crazy someone. Ruby steeled herself for the hundreds of handshakes and hushed greetings she would endure throughout the day. Then she brought William’s body home to the estate and said one final goodbye as he was laid to rest in the family cemetery, right next to Alice.

It was the last time Ruby had ever been to the graveyard and one of the last times she’d ever set foot in town.

From her window seat, Ruby searched the distant horizon in the direction of the cemetery. It was tucked away in a grove of mulberry trees a few hundred yards from the house, hallowed ground for every Hurst family member who had lived and died on this property since the Gilded Age.

Ruby never wanted to see it again. Not until her own aged body was shut inside a wooden box and lowered quietly into the earth, her secrets finally at peace with her.